By John S. Shackford

Welcome back from summer break. Birdwise we are already well into fall migration. Let me ramble a bit. Spring and fall are the times for long lists of birds in Oklahoma because of the addition of those species that are only transients here. Spring is the “easy” identification season, when males usually show their most striking plumage. Fall is the “hard” identification season—dull plumaged males, duller females and really dull young of the year, especially if you are talking warblers.

Welcome back from summer break. Birdwise we are already well into fall migration. Let me ramble a bit. Spring and fall are the times for long lists of birds in Oklahoma because of the addition of those species that are only transients here. Spring is the “easy” identification season, when males usually show their most striking plumage. Fall is the “hard” identification season—dull plumaged males, duller females and really dull young of the year, especially if you are talking warblers.

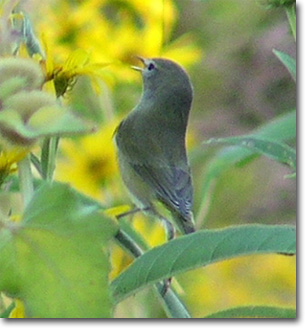

In central Oklahoma September is when southward migration gets into full swing for many transitory species, and one such bird is the Nashville Warbler (Vermivora ruficapilla). Much of the Nashville Warbler population nests in Canada—north of the United States—and winters in Mexico, many passing over Oklahoma in between the two areas. It nests on the ground and usually lays 4-5 eggs in a first nesting; it is known to be parasitized by the Brown-headed Cowbird.

Recently, in reading A.C. Bent’s Life Histories of North American Wood Warblers, I was surprised to find that when the Nashville Warbler was first discovered, and for a number of years following in the 1800’s, it had been considered a rare species. It was something of a shock to learn that this was an “edge” species; edge is where two habitats abut each other, such as the junction between forest and meadow. In the 1800’s Canadian forests were not as fragmented as today. Most warbers are not benefited by fragmentation of habitat, but apparently the Nashville Warbler is—the exception to the rule. So now, apparently, there are more Nashville Warblers than when the Canadian forests were pristine.

A couple of my favorite birding stories relate to the Nashville Warbler. It was a species that led to Warren Harden and me becoming longtime friends. I had seen some gray headed warblers one fall many years ago, and thought there might be a possibility that one or more could have been Mourning Warblers. Dr. Sutton suggested that Warren and I try to band some of these, primarily to determine if they were Mourning Warblers. It turned out that most, probably all, I had seen were Nashville Warblers, not Mourning Warblers, but it allowed Warren, Doc, and me to become better acquainted with each other, and ultimately, long-time friendships; we also became better acquainted with this migratory species. Only looking at that event many years in hindsight did the true significance of that as a day of friendship come so clear.

The second story also involved Warren Harden. He used to have a band of about 10 subpermittee birdbanders, and we usually had good luck when we were banding. We always had a good time. Some of Warren’s subpermittees were banding at Lake Overholser, north of the coffer dam, on 26 September 1980. We caught a Nashville Warbler, banded and released it. The following year Warren received a letter from the U.S. Department of the Interior Bird Banding Laboratory, stating that this Nashville Warbler had been recovered during March, 1981, at the village of San Pedro de Honor, in the Province of Nayarit, western Mexico. Curious about the band recovery, Warren wrote the Banding Laboratory for more information. We received a letter in Spanish, together with translation, which read: “At San Pedro de Honor, Nayarit, a 9 year old child was walking under the trees with a slingshot and little birds were in the trees. The child killed one of them and it had a band………..” The distance from site of banding in Oklahoma to site of collecting in Nayarit, Mexico was 1050 miles, the bird had survived over 5 months, and because Nayarit is on the west coast of Mexico, the warbler must have crossed the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains to get to Nayarit.. It was a lot to learn from one very small bird.